By Amy Stewart

One frequently asked question the Empowerment Collaborative receives is, “Where do you projects come from?”

Project ideation can seem like an intimidating task because the concept of authentic learning opens a whole world of challenges for students. How do we filter down to what is relevant to students, appropriately challenging and standards-based for the grade level, and a worth task that will challenge students to inquire, iterate, experiment, and create while they learn?

In his, “Introduction to Poetry”, poet Billy Collins described teaching poetry as an art: “I ask them to take a poem and hold it up to the light like a color slide or press an ear against its hive. I say drop a mouse into a poem and watch him probe his way out, or walk inside the poem’s room and feel the walls for a light switch. I want them to water ski across the surface of a poem waving at the author’s name on the shore.” He contrasted this to the ways of thinking the students held when they came to him, having experienced years of the “systematized” way of teaching students to approach a poem: “But all they want to do is tie the poem to a chair with rope and torture a confession out of it. They begin beating it with a hose to find out what it really means.” Forgive me for reaching into my literary roots, but this contrast between the art of learning and the system of traditional teaching illustrates an important point: it is in the wonder, the exploration, and the mess that our students learn how to think rather than how to execute sets of tasks.

Sometimes, in an effort to make a system out of an art, we take the authenticity out of project planning.

Currently, teams of teachers in Calhoun and Fayette counties are working with the Empowerment Collaborative to develop projects, and the process of ideation has been distinctly different in each location. Of course, there are components that should be considered and planned for every project. There is a real value for planners, organizers, and lists to hold teachers and teams accountable to the best practices of project-based learning. But in the process to identify a project idea, there are many ways to enter the conversation.

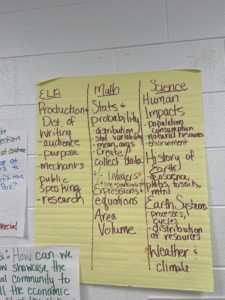

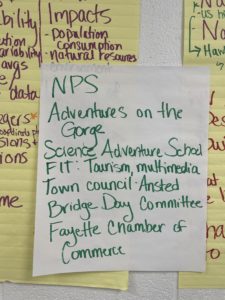

At Midland Trail High School, the sixth grade teaching team started by identifying the deep standards that still need to be taught in this year that could form the basis of a project in each content area. They also brainstormed the things that interest and excite their  students. Thirdly, they identified assets, needs, and challenges of their community. With these working lists, the teachers discussed potential intersections; by combining major standards from math, science, social studies, and English, student interests, and community needs, interesting challenges emerged. The student interest lens revealed that students love hands-on activities, and they loved experiences they had with the National Park Service in the summer. Visualizing the major standards as a collection across contents uncovered rich opportunities to combine persuasion, data collection, analysis, and application, and human impacts of the local ecosystem. Add to this the fact that their community is in the midst of a unique challenge: the New River Gorge on the other side of the county was recently named a National Park, which has brought economic benefits to that side of the county, but the tourism increase has not had a positive impact on the rest of the county. With this intersection of ideas, they saw an opportunity for students to develop and pitch real solutions to real audiences that would

students. Thirdly, they identified assets, needs, and challenges of their community. With these working lists, the teachers discussed potential intersections; by combining major standards from math, science, social studies, and English, student interests, and community needs, interesting challenges emerged. The student interest lens revealed that students love hands-on activities, and they loved experiences they had with the National Park Service in the summer. Visualizing the major standards as a collection across contents uncovered rich opportunities to combine persuasion, data collection, analysis, and application, and human impacts of the local ecosystem. Add to this the fact that their community is in the midst of a unique challenge: the New River Gorge on the other side of the county was recently named a National Park, which has brought economic benefits to that side of the county, but the tourism increase has not had a positive impact on the rest of the county. With this intersection of ideas, they saw an opportunity for students to develop and pitch real solutions to real audiences that would  engage the students in using math to identify possibilities and science to understand the consequences, using English language arts to craft a message, and using social studies to leverage geology, geography, and history as reasons people travel and explore the area. As we tried to get clarity on the end product and experience, there was some debate over whether we should specify that students will create one sellable product, a video, or a specified series of advertisements. The teachers decided that they could provide a more empowered experience for students to make choices by leaving the expectations for “products” open as a marketing campaign so that teachers can provide scaffolding and students can seek to understand the problem and the customer, organize their thinking, research, and use the information they have to propose approaches that they believe would bring tourists in and engage the locals in the businesses and natural offerings in their community.

engage the students in using math to identify possibilities and science to understand the consequences, using English language arts to craft a message, and using social studies to leverage geology, geography, and history as reasons people travel and explore the area. As we tried to get clarity on the end product and experience, there was some debate over whether we should specify that students will create one sellable product, a video, or a specified series of advertisements. The teachers decided that they could provide a more empowered experience for students to make choices by leaving the expectations for “products” open as a marketing campaign so that teachers can provide scaffolding and students can seek to understand the problem and the customer, organize their thinking, research, and use the information they have to propose approaches that they believe would bring tourists in and engage the locals in the businesses and natural offerings in their community.

At Calhoun Middle School, I have been working with two eighth grade math teachers and a West Virginia history teacher to identify a project idea. We were, honestly, stumped to find an idea that would engage students and be content-rich for both courses. Later in the day, I ate lunch in a room with a small group of eighth graders and their science teacher. We struck up a conversation about what challenges they would find interesting to tackle in West Virginia history and what they love about West Virginia. One student brought up her love of West Virginia’s “prettiness”. She likes photography and was expressing that West Virginia provides a lot of opportunities to take great photos. I remembered a conversation I’d had about a set of “Almost Heaven” swings that Nicholas County Career Center students had made for states in the nine tourism regions of West Virginia. A project was born out of this conversation- the students recognized the value of “Instagram-worthy” spots and surmised that if tourists knew how to find the swings and what else was in the area to do, they could draw tourists to the locations simply for the picture. They were curious about how the increase in visitors to an area could impact that location. The students brainstormed potential project products and deliverables for a presentation, experiences that would be necessary or interesting to learn or research as they work on the project, and even concepts in math and social studies that should be taught. The students went back to their West Virginia studies teacher and filled him in, asking if they would really be able to do that project. A few weeks later, their teachers are currently finalizing plans to launch this project, but one of the greatest project hurdles is already jumped: they have students who feel ownership of the project and are gathering others to be interested in the problem.

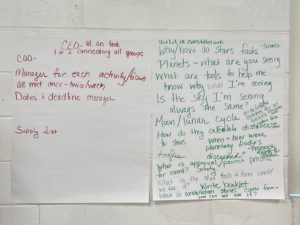

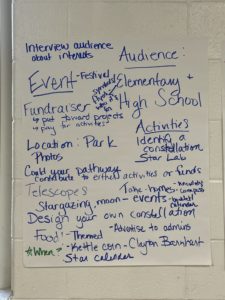

Last year, two students in Calhoun County’s middle school were invited to join a team with a teacher and six local business leaders to brainstorm a project idea. Through mapping of  the local assets, student interests, and local needs as a collaborative group, they identified a project idea: to expand local youth knowledge of the community park and its resources to enjoy their uniquely dark skies. The two students went back to the school to expand their

the local assets, student interests, and local needs as a collaborative group, they identified a project idea: to expand local youth knowledge of the community park and its resources to enjoy their uniquely dark skies. The two students went back to the school to expand their

student team from two students to ten students representative of the school’s career exploration groupings. That leadership group met to brainstorm potential project outcomes, deliverables, audience, timing, and what content they would need to learn in order to successfully complete the project. This approach invited students into nearly every phase of the project planning. That is not always possible, but we hold it as a goal to open our eyes for new opportunities to empower students to direct their learning.

student team from two students to ten students representative of the school’s career exploration groupings. That leadership group met to brainstorm potential project outcomes, deliverables, audience, timing, and what content they would need to learn in order to successfully complete the project. This approach invited students into nearly every phase of the project planning. That is not always possible, but we hold it as a goal to open our eyes for new opportunities to empower students to direct their learning.

Ideas come from many sources. The challenge is in seeing opportunities, engaging students as drivers in as many points in the process as possible, and then empowering those students to engage in their school as a workplace to try, struggle, make mistakes, learn, and demonstrate their skills and knowledge deeply and authentically.

Cheers!

Thanks!